Professionals and Clinicians

What is Brain Injury?

The brain is the control center of everything we think, do, and experience. It is responsible for maintaining our bodily functions, planning and executing our movements, processing inputs from our senses, determining our reactions to stimuli, storing and retrieving our memories, and processing our emotional responses. So, what happens when the brain is injured?

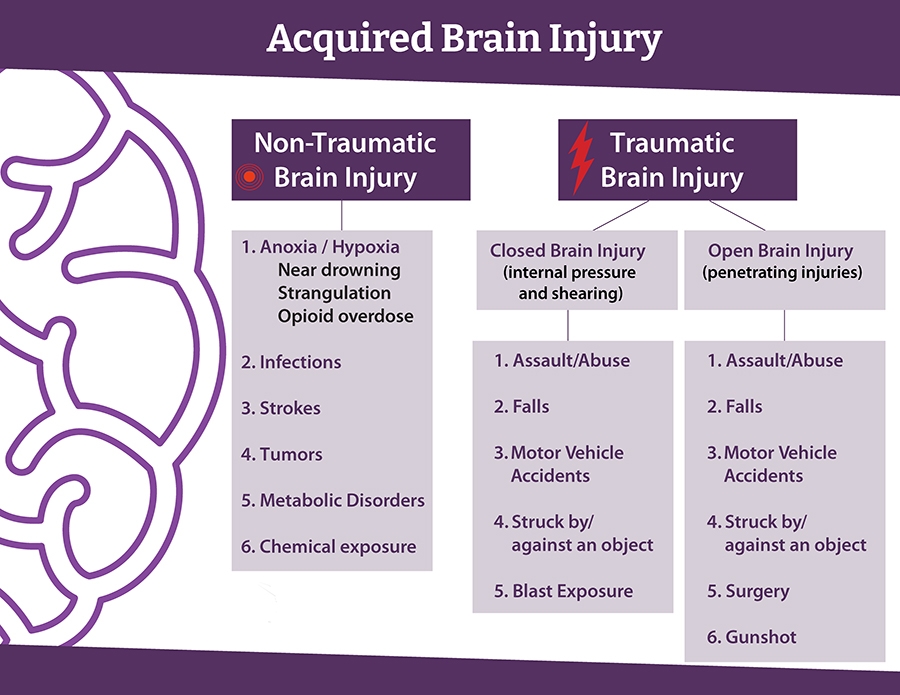

Acquired Brain Injury

Your Subtitle Goes Here

An acquired brain injury (ABI) is any insult or injury to the brain that occurs after birth and results in a change of the brain’s chemical makeup and neuronal activity. The ABI label does not include congenital brain injuries or malformations, developmental disabilities such as Down syndrome, or degenerative brain diseases, such as Multiple Sclerosis and Alzheimer’s; however, it does cover a broad range of injury types and causes.

Traumatic Brain Injury

Your Subtitle Goes Here

The most commonly recognized ABIs are Traumatic Brain Injuries (TBI), which are caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head from an outside force. Common causes of TBI include falls, motor vehicle accidents, being struck by or against and object, and violent assaults. If the skull is penetrated, this is called an “open” brain injury, but a non-penetrating, “closed” brain injury can be just as devastating. Even if the head does not make contact with another object, the brain can also sustain injury from violent shaking, such a coup-contra-coup and diffuse axonal injuries.

Examples include a rapid vehicle roll-over, a sudden stop, or an explosive IED blast These incidents can cause the brain to strike against the interior of the skull, or delicate axonal fibers key for neuronal communication can be sheared. These kinds of closed Traumatic Brain Injuries can often go overlooked and undiagnosed, even as they cause negative lifelong outcomes for the survivor.

Non-traumatic Brain Injury

Your Subtitle Goes Here

Non-traumatic brain injuries can be equally life-altering, and include strokes, tumors, infections, metabolic disorders, chemical exposure, and hypoxia or anoxia. Hypoxic (insufficient oxygen) and anoxic (lack of oxygen) brain injuries can occur due to heart failure, near drowning, strangulation, and drug overdose. If a person requires surgery for any of these issues, the surgery itself may be considered a TBI, as the skull is penetrated, and surgical instruments make contact with brain tissue.

A head injury may be difficult to initially detect, as neurological dysfunction most commonly presents itself as the brain starts to heal, a process that does not follow a specific timeline and is unique to the individual.

The process often appears as follow: An injury impacts the brain, which affects the brain’s communication with internal systems and interactions with its environment, which in turn changes how the person interacts with their community.

Because the microscopic damage to brain cells may not result in an easily spotted disability, brain injuries are often referred to as an “invisible injury.”

What Outcomes Will a Survivor Experience?

Just as every person is different, every brain injury is equally unique. Since different lobes, hemispheres, and structures of the brain are responsible for different tasks, the location of the injury may give the medical team an idea as to what kinds of symptoms to look for, but brain injuries are not often easily predictable. A person may lose some or all of their ability to process sensory information such as sight, hearing, or smell. They may experience problems with falling asleep or staying awake. They may have difficulties with balance or motor skills, like planning and executing movements. They may lose their ability to regulate their body temperature or know when they are hungry. They may no longer be able to interpret spoken or written speech or may have trouble forming language themself. They may experience chronic pain, dizziness, confusion, sensory sensitivity, or seizures. They may even experience many of these sequelae simultaneously.

For survivors of TBI in particular, one of the most commonly affected areas is the frontal lobe. This is due to the fact that most blows occur to the front of the head. Additionally, the boney protrusions inside the skull around the eye sockets can penetrate brain tissue when they are bumped against during any kind of jolt, regardless of where the initial impact to the head was located.

The frontal lobe is responsible for our executive functions, which encompass our working memory, mental flexibility, and self-control. Someone with frontal lobe damage may therefore have a range of deficits that can make it difficult to maintain relationships, reach goals, and function in society. They may have difficulty paying attention, following directions, making plans, struggling with initiation, organization, prioritization, and follow-through. They may also have problems with emotional regulation, disinhibition, self-reflection, and empathy.

While these symptoms can have damaging effects on a survivor’s relationships and ability to maintain employment and housing stability, brain injury as the culprit of these impacts are often overlooked, ignored, disbelieved, forgotten, and therefore go unaddressed and untreated, even by seasoned medical professionals.

How Common is Brain Injury?

In the United States, it is estimated that 230,000 people each year are hospitalized and survive after a traumatic brain injury. 80,000 – 90,000 of those go on to experience long-term injury-related disability. But these figures are incomplete. They do not take into account brain injuries that are treated through the VA, pediatric, or tribal hospitals, those treated at an urgent care clinic or by a general practitioner, or those who don’t receive treatment at all. They also do not include non-traumatic brain injuries, such as strokes, tumors, brain infections, and anoxic/hypoxic injuries. The true scope of the effects of brain injury on a national and global scale is currently unknown.

The CDC’s National Center for Injury Prevention and Control estimates that 5.3 million people in the U.S. are currently living with disability as the result of a TBI. If you are working with certain at-risk populations, this number is likely higher.

From 2000 to 2011, 4.2% of United States Military Service Members were diagnosed with a TBI. While enemy fire and shrapnel were the cause of some of these injuries, training accidents, motor vehicle crashes, falls, and assault also contribute to higher risk for our service members. Often overlooked is blast exposure, where simply being too close to an explosive force can cause the brain to reverberate inside the skull and cause injury. Post-Traumatic Stress, while not a physical brain injury, is experienced by many of our Veterans and can also change the brain’s neuronal activity, resulting in many symptoms similar to a TBI.

Survivors of domestic violence, interpersonal violence, and child abuse also have a higher prevalence of TBI than the general population. One study found that 81% of women who seek help for Intimate Partner Violence (IPV) have suffered at least one brain injury, while 81% have been strangled, which can cause anoxic or hypoxic brain injury. Similarly, 92% of sex trafficking survivors experience physical violence, with most blows directed at the head and face to hide tell-tale signs of abuse.

Misuse of drugs or alcohol can put a person at higher risk for brain injury, including through accident, violence, and overdose. Slower reaction times, reduced inhibition, and poor decision-making can put people into myriad dangerous situations. Survivors of brain injury may be likely to self-medicate with drugs or alcohol and may have a harder time moderating their use. These factors contribute to the estimated 38% to 63% of patients in treatment for substance use disorders who report a history of at least one TBI.

It is estimated that the lifetime prevalence of moderate or severe TBI among those experiencing homelessness is 22.5%. Of homeless TBI survivors, 70% – 90% experienced their first brain injury prior to becoming homeless. People experiencing homelessness are also more vulnerable to accidents and violence. With only about 40% of brain injury survivors able to return to work within two years of their injury, there is an evident correlation between brain injury and result for becoming part of a vulnerable population.

Similar statistics exist within the incarcerated and justice-involved populations. Researchers estimate inmates may be up to 10 times more likely to be living with a brain injury than the general population. Nearly a third of TBI survivors report some involvement with the criminal justice system within five years of their injury. This may in large part reflect the impulsivity, disinhibition, and emotional dysregulation that can often occur post-brain injury.

Learn more about Vulnerable Populations:

Learn more about Vulnerable Populations:

How Can Brain Injury Be Overlooked?

Even among medical professionals, there exists an unfortunate lack of understanding of brain injury. While the brain can heal, and neuroplasticity enables the brain to form new neural connections to compensate for illness or injury, this process does not restore the brain to its original state and does not guarantee complete recovery to pre-injury functionality. It is also not commonly understood that when a person experiences multiple brain injuries, this will generally have an exponential effect on symptoms, rather than simply an additive effect.

There are also disproved myths and misconceptions that still pervade the general medical community. For example, it is commonly believed a brain injury in a young child is less harmful because a young brain has a greater ability to heal, much like if they were to break a bone. This is inaccurate – injury to a younger brain can actually delay or halt brain development, and a child can miss or struggle with important developmental milestones. This and other inaccurate beliefs about brain injury can contribute to misunderstanding of survivors’ needs, resulting in poorer outcomes for then.

Most people have heard of concussion, but not everyone recognizes it as a brain injury. Though classified as a mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI), the associated symptoms often result in anything but mild consequences. This misinterpretation can paint a survivor as exaggerating their condition and prevent them from receiving appropriate care. There is unfortunately a lot of misinformation regarding diagnosis and treatment. Contrary to popular belief, a person can have a concussion without losing consciousness. Also, the idea that a person must be kept awake after a concussion is untrue— the exact opposite is actually true, as sleep is essential for recovery. In the case of a sports-related TBIs, some believe it is okay for athletes to return to play as soon as they say they “feel fine”. Unfortunately, doing so before being cleared by a designated professional can lead to further detrimental outcomes, such as post-traumatic headache, memory loss, or the life-threatening second-impact syndrome.

When a person experiences complex trauma, such as in a motor vehicle accident, medical staff primarily focus on triaging the most evident urgent issues in an effort to keep the patient alive. They need to prioritize actions that will stop internal bleeding or damage to organs. Likewise, if someone experiences cardiac or respiratory arrest, the damage caused by lack of blood or oxygen to the brain might well go unaddressed. Once the patient is stabilized, possible head injury may still go unnoticed, especially if there is no obvious head wound or indicators present in a CT scan or MRI.

Brain injury can also be overlooked because symptoms do not always emerge at onset of injury. Sometimes, they will not materialize for days, weeks, months, or even years post-injury. A patient may present with a relatively new emotional/behavioral issue, for example, but the causative injury has been long forgotten. Brain injuries can sometimes fall off a patient’s medical history, making it difficult to recognize the connection to their current symptoms and previous injury.

Especially within certain populations, symptoms of brain injury can often be mistaken primarily as mental illness. While brain injury survivors and people with mental illness can present with very similar behaviors, and the two can certainly cooccur, it is imperative to distinguish one from the other to provide effective treatment. Misdiagnosis of brain injury as mental illness can have detrimental outcomes, which can include experiencing adverse effects of inappropriately prescribed medications and losing faith in the efficacy of medical and mental health services. Misidentification notwithstanding, survivors of brain injury are more likely to experience clinical depression, anxiety, and emotional dysregulation.

Given the misunderstandings within the medical community, brain injury is even less understood by the general population. We don’t know how many brain injuries occur every day that go unrecognized or are deemed too minor to necessitate medical intervention. We must also recognize that healthcare in our country is prohibitively expensive for many of our citizens, and some who do want treatment are able to get it. Systemic inequities can impose additional barriers on People of Color, LGBTQ+ individuals, and other marginalized communities.

Brain injury is often called “the invisible disability”. Although someone physically “looks fine,” and is able to walk and talk normally, this does not mean they are free of deficits and challenges that impact their life greatly. Many survivors are disbelieved, even by their own families, and may hear things such as, “You’re just not trying hard enough,” or “I miss the old you; when will you normal again?” This invalidation of a survivor’s struggle only serves to demoralize and isolate them. When you are working with a patient, asking questions, and listening to their answers will greatly increase the chance they will be open and honest with you, and trust your medical advice is in their best interest.

Brain Injury Survivors & Their Families

How Can I Know If My Patient Has a Brain Injury?

For acquired brain injuries like stroke and brain tumors, a CT scan or MRI can often help determine details such as location and size. While these technologies can be helpful in detecting signs of some moderate and severe TBIs, they are often unable to detect damage at the micro level most commonly found in “mild” TBIs.

While there is no current test that can definitively diagnose a TBI, there are fortunately several screening tools to identify lifetime history of TBI. Some of the ones you will most likely come across include:

- The OSU TBI I.D. is considered the gold standard of TBI screening by the National Association of State Head Injury Administrators (NASHIA). It includes a short three-step interview process for recording data of past and recent head injuries.

- HELPS is an acronym: (Head ever been hit/injured; Ever seen in ER for head injury; Loss of consciousness; Problems or symptoms that disrupt daily life; and Significant sickness, illness, surgery).

- ImPACT for Athletes provides a baseline and post-injury test to determine presence and severity of a concussion.

- MACE II, or the Military Acute Concussion Evaluation, is a fast way to access concussion symptoms in active-duty servicemen and women.

One of the best assessments for addressing the multi-faceted symptoms of a brain injury is a Neuropsychological Evaluation. This intensive battery of tests evaluates a person’s cognitive and emotional capabilities, and is typically administered by a neuropsychologist. While the aforementioned screening tools are relatively brief to conduct, Neuropsychological Evaluations can take four or more hours to complete. The results can help determine which treatments and therapies might be most beneficial for the survivor.

While you should never judge a book by its cover, there are some physical clues that may be indicative of a head injury. Look for:

- Scars on the head that may indicate injury or surgery

- Chipped or missing teeth

- Broken nose

- Spinal cord injury

- History of suicide attempts

- Stories of the “long forgotten head injury,” such as falling from a ladder, getting punched in the face, a terrible car accident, etc.)

- A history of Special Education Classes during grade school

Once you have identified that your patient might have experienced a brain injury, do not assume to understand all their capabilities and deficits or that the injury is “too old” for them to benefit from care. Talking with the patient, as well as the family and caregivers who know them best, will provide a clearer picture of their needs, as well as next steps. You may also find it useful to employ additional screenings to address other commonly affected determinants of health.

One such tool is the Mayo-Portland Adaptability Inventory

How Might a Brain Injury Impact Treatment?

A person with a brain injury may have difficulty with setting and keeping appointments, bringing the appropriate paperwork, or accurately describing their symptoms. They may struggle to follow a treatment plan, take their medications correctly, or report back on a treatment’s efficacy. They may not understand the medical concepts explained to them, but may not want to admit it and ask for clarification. They may also be more easily fatigued, frustrated, or overwhelmed, and could give up on treatment altogether. There are, fortunately, things you can do to better accommodate a patient with a brain injury.

What Can I Do to Accommodate Brain Injury Survivors and Families?

For survivors of brain injury, their attention, concentration, and mood can be strongly affected by their environment. What kind of environment do you meet your patients in? Is it neat or cluttered? Are there distracting sounds or noise? Are there florescent lights that could cause headaches? Try to reduce as many distractions and unpleasant factors as possible to foster concentration, trust, and connection in your patients.

Routines and schedules become very important for survivors of brain injury and the ones who care for them. Mental flexibility can be limited, so knowing what to expect and when provides stability and consistency. Last minute changes in a scheduled appointment, or any other unexpected changes, may throw a wrench in a person’s routine and cause distress. Strive to schedule appointments well in advance and try not to make abrupt changes to the time or staff they are expecting to see. Do your best to be predictable and dependable. It is also a good idea to confirm the appointment with them beforehand.

Sometimes brain injury can affect a survivor’s personality in ways that can make it more difficult to work with them. A person who has survived a brain injury may appear to lack empathy and be preoccupied with their own situation without considering others. This can manifest as thoughtless, hurtful remarks or unreasonable, demanding requests. If you encounter this behavior, it is okay to kindly cue the person to recognize thoughtlessness and remind them to practice appropriate behavior. Understand that a survivor’s awareness of the feelings of others may have to be relearned and can take time.

Other behaviors you may encounter are perseveration and confabulation. In practice, perseveration looks like the involuntary, inappropriate repetition of a behavior, and is most likely to occur when a survivor is learning a new task, or feeling anxious. You may notice them performing the same task or telling you about the same information over and over. You can help by finding a verbal or physical cue to bring attention to the behavior, or by redirecting them to another thought or task.

Confabulation often seems as though a person is lying or making things up. However, a survivor dealing with confabulation does not realize their brain is providing incorrect information. After a brain injury, both short and long-term memory may be affected. Confabulation is the brain’s attempt to make sense of past thoughts and memories, which may express anachronistically. Some psychotherapy methods may be effective in treating the confabulation. Familiar surroundings and objects linked to memories such as photobooks, letters, emails, and keepsakes can be used to help orient the survivor. Keeping and reviewing a journal may also be beneficial.

When communicating with your patients about their health and treatment, it is vital they and their caregiver understand your instructions for treatment to be successful. P.R.I.M.E.R. is an acronym with helpful best practice tips for successful patient/provider interactions.

- P -Pace communications (once concept at a time)

- R – Repeat important concepts

- I – Illustrate using concrete examples

- M – Memory Aids

- E – Environmental modifications (including the involvement of caregivers)

- R – Re-direction is sometimes necessary to move client to problem-solve

Another helpful acronym is R.O.W.B.O.A.T.S.

- R– Reduce the amount of info given at one time

- O – One instruction at a time, in simple short chunks

- W – Written and verbal formats when possible

- B– Breaks are helpful – avoid overwhelming the individual

- O – Often is better, routines help

- A – Ask the person to repeat what you said to ensure understanding

- T – Take the time and go at a slower pace

- S– Simple and organized info is best

Additional Information

Make a Referral

Do you have a patient or client who may need our complimentary services? To access our support team email info@biaaz.org or call (602) 508-8024

Resource Directory

Professionals who specialize in services to those with brain injury can apply to be part of our Resource Facilitation Database.

APPLICATION

The Brain Injury Association of Arizona is a statewide organization committed to creating a better future through brain injury prevention, advocacy, and education. We support, connect, and empower survivors of brain injury and their caregivers on their journey to recovery. Our work began as a grassroots effort and has grown to a strong statewide presence for survivors and the professionals who work with them.

We follow five pillars in our work – support, educate, advocate, prevent and inspire. Thank you for your interest in supporting our work.

The Brain Injury Association of Arizona reserves the right to edit information for clarity, brevity and content and to publish this information in a variety of media, subject to confidentiality issues.

The Brain Injury Association of Arizona provides a variety of resource information to people who inquire. We do not recommend or endorse any particular organization or individual and are not liable for services rendered.

Brain Injury Association of Arizona

5025 E. Washington St, Ste 108

Phoenix, Arizona 85034

QCO CODE: 22360

EIN 94-2937165

CALL

HELP LINE

(888) 500-9165

(602) 508-8024 - OFFICE

(602) 508-8285 - FAX

FOLLOW US

contact us

privacy policy

terms & conditions